Psychoanalytic

Psychoanalysis refers to the theories and therapeutic techniques applied to the unconscious mind and its impact on everyday life. These theories and techniques inform treatments for mental disorders.[106][107][108] Psychoanalysis originated in the 1890s, most prominently with the work of Sigmund Freud. Freud’s psychoanalytic theory was largely based on interpretive methods, introspection, and clinical observation. It became very well known, largely because it tackled subjects such as sexuality, repression, and the unconscious.[109] Freud pioneered the methods of free association and dream interpretation.[110][111]

Psychoanalytic theory is not monolithic. Other well known psychoanalytic thinkers who diverged with Freud include Alfred Adler, Carl Jung, Erik Erikson, Melanie Klein, D.W. Winnicott, Karen Horney, Erich Fromm, John Bowlby, Freud’s daughter Anna Freud, and Harry Stack Sullivan. These individuals ensured that psychoanalysis would evolve into diverse schools of thought. Among these schools are ego psychology, object relations, and interpersonal, Lacanian, and relational psychoanalysis.

Psychologists such as Hans Eysenck and philosophers including Karl Popper sharply criticized psychoanalysis. Popper argued that psychoanalysis had been misrepresented as a scientific discipline,[112] whereas Eysenck advanced the view that psychoanalytic tenets had been contradicted by experimental data. By the end of the 20th century, psychology departments in American universities mostly marginalized Freudian theory, dismissing it as a “desiccated and dead” historical artifact.[113] Researchers such as António Damásio, Oliver Sacks, and Joseph LeDoux, and individuals in the emerging field of neuro-psychoanalysis, have defended some of Freud’s ideas on scientific grounds.[114]

Existential-humanistic theories

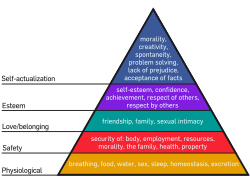

Humanistic psychology, which has been influenced by existentialism and phenomenology,[116] stresses free will and self-actualization.[117] It emerged in the 1950s as a movement within academic psychology, in reaction to both behaviorism and psychoanalysis.[118] The humanistic approach seeks to view the whole person, not just fragmented parts of the personality or isolated cognitions.[119] Humanistic psychology also focuses on personal growth, self-identity, death, aloneness, and freedom. It emphasizes subjective meaning, the rejection of determinism, and concern for positive growth rather than pathology. Some founders of the humanistic school of thought were American psychologists Abraham Maslow, who formulated a hierarchy of human needs, and Carl Rogers, who created and developed client-centered therapy.

Later, positive psychology opened up humanistic themes to scientific study. Positive psychology is the study of factors which contribute to human happiness and well-being, focusing more on people who are currently healthy. In 2010, Clinical Psychological Review published a special issue devoted to positive psychological interventions, such as gratitude journaling and the physical expression of gratitude. It is, however, far from clear that positive psychology is effective in making people happier.[120][121] Positive psychological interventions have been limited in scope, but their effects are thought to be somewhat better than placebo effects. The evidence, however, is far from clear that interventions based on positive psychology increase human happiness or resilience.[120][121]

The American Association for Humanistic Psychology, formed in 1963, declared:

Humanistic psychology is primarily an orientation toward the whole of psychology rather than a distinct area or school. It stands for respect for the worth of persons, respect for differences of approach, open-mindedness as to acceptable methods, and interest in exploration of new aspects of human behavior. As a “third force” in contemporary psychology, it is concerned with topics having little place in existing theories and systems: e.g., love, creativity, self, growth, organism, basic need-gratification, self-actualization, higher values, being, becoming, spontaneity, play, humor, affection, naturalness, warmth, ego-transcendence, objectivity, autonomy, responsibility, meaning, fair-play, transcendental experience, peak experience, courage, and related concepts.[122]

Existential psychology emphasizes the need to understand a client’s total orientation towards the world. Existential psychology is opposed to reductionism, behaviorism, and other methods that objectify the individual.[117] In the 1950s and 1960s, influenced by philosophers Søren Kierkegaard and Martin Heidegger, psychoanalytically trained American psychologist Rollo May helped to develop existential psychology. Existential psychotherapy, which follows from existential psychology, is a therapeutic approach that is based on the idea that a person’s inner conflict arises from that individual’s confrontation with the givens of existence. Swiss psychoanalyst Ludwig Binswanger and American psychologist George Kelly may also be said to belong to the existential school.[123] Existential psychologists tend to differ from more “humanistic” psychologists in the former’s relatively neutral view of human nature and relatively positive assessment of anxiety.[124] Existential psychologists emphasized the humanistic themes of death, free will, and meaning, suggesting that meaning can be shaped by myths and narratives; meaning can be deepened by the acceptance of free will, which is requisite to living an authentic life, albeit often with anxiety with regard to death.[125]

Austrian existential psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl drew evidence of meaning’s therapeutic power from reflections upon his own internment.[126] He created a variation of existential psychotherapy called logotherapy, a type of existentialist analysis that focuses on a will to meaning (in one’s life), as opposed to Adler’s Nietzschean doctrine of will to power or Freud’s will to pleasure.[127]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychology#Major_schools_of_thought